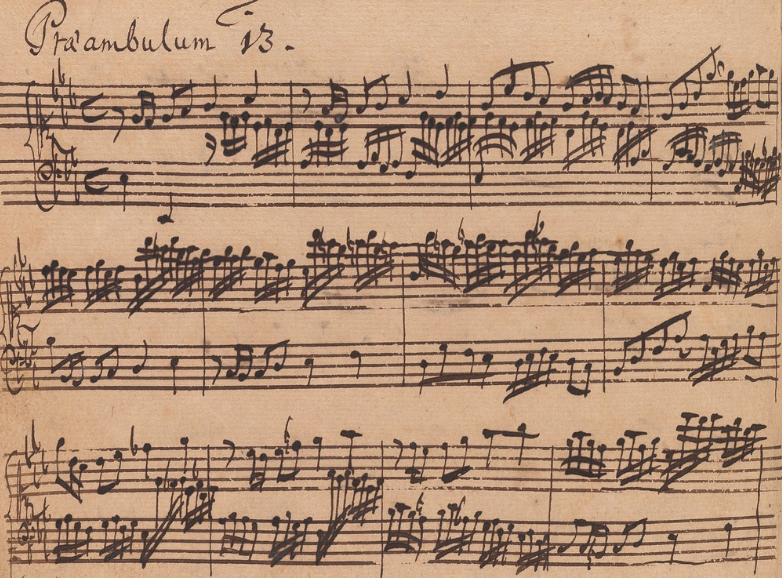

Invention in E flat major

This is one of those inventions that truly begins to grapple with mastery, confidence, and a profound sense of pride. The sequences are crystal clear, the tone fiercely intense, and although it's written for just two voices, the questions and answers become so intricately intertwined that at times it feels like there are more than two voices—especially if you sustain certain notes or add the slightest embellishments.

The true essence is remarkably condensed and concise, which is precisely what makes Bach's genius so impressive. Right from the start, the left hand declares everything in that bold "Bam bum"—that's all it takes. It instantly seizes your attention, lays out the essential material, and hooks you until the very end. From there, the piece simply unfolds and develops organically, much like a tree growing from its seed. The opening left-hand statement is the seed, and Glenn Gould plays it with such proud, assured confidence that it makes the entire structure feel utterly intuitive and self-evident.

Now that the left hand has boldly stated the most essential motif—setting the foundation—its counterpart emerges to complete what was only partially expressed at first. You hear it as something like "da do dam dam brobm bam."

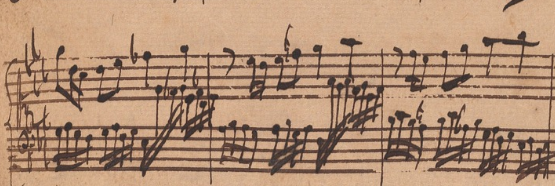

Then it repeats the same idea once more, priming your ear and building anticipation. A third time it appears, making you long for the clear, straightforward sequence to continue on a fourth—but no! Bach teases you instead; that's merely a playful feint, holding back the true core material for later.

And then comes a gorgeous reversal: the same motif suddenly shifts to the left hand, allowing you to hear it anew in that deeper register, as if the voices have traded places in a delightful contrapuntal dance.

And now comes one of the most thrilling moments: Bach heightens the excitement even further by presenting the sequence for a third time, making the listener almost ache for that longed-for fourth repetition. The anticipation builds to an intense peak—you can practically feel the music demanding resolution, craving that final statement to complete the pattern.

Yet, once again, Bach withholds it. There is no fourth appearance. The silence where it should have been speaks louder than any note, leaving the tension hanging deliciously unresolved and pulling you deeper into the piece's magnetic pull

And very effectively so: just as the music arrives at its moment of highest tension, Bach masterfully shifts the modality—altering the harmonic color in a subtle yet piercing way. This single change releases the accumulated pressure in the most satisfying manner, transforming the built-up yearning into a profound sense of resolution and relief, while still preserving the piece’s fierce, concentrated energy.

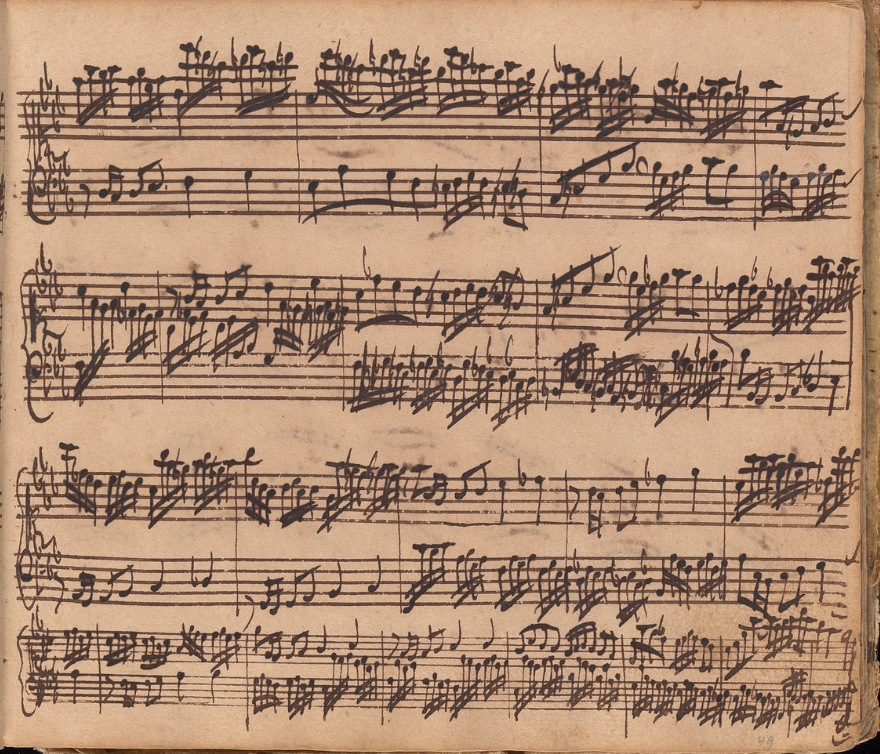

Finally, the tension eases, and the music begins a gentle, gradual descent—slowly, deliberately—much like an airplane preparing for landing, with subtle ascents and descents mirroring the plane's final approach. The music itself seems to "land" softly as well. Glenn Gould masterfully demonstrates this through his control of dynamics (volume and intensity), shaping the phrasing to create that sense of descent and resolution.

This quality feels almost inherent in the music, even though Bach's original keyboard instruments (like the harpsichord or clavichord) weren't designed for the same level of expressive dynamic variation as a modern piano. Gould brings it out vividly, especially on the second page of the score—particularly toward the end, where the descent becomes most pronounced and evocative.